The Beyond Growth event, held on Nov 3 at Grant Thorton on Fanshawe Str, Auckland CBD, and hosted by Degrowth Aotearoa, started promisingly with karakia, kai and networking.

The vibe in the room was alive, and small pockets of people gathered around sumptuous catering to connect.

Our name tags were made of upcycled cans with safety pins, and figuring out how to affix mine gave me the perfect opportunity to connect with Dr. Naomi Pocock, a TOP candidate in the recent election.

These small details – recognising the importance of prayer, shared food, and providing name tags that embodied the kaupapa of the event boded well.

However, the format of the day was mostly talking heads, some of whom were heartfelt and engaging, some of whom delivered facts with little narrative or sense-making, and some who were passionate about their particular niche, but worked in a way that I felt wasn’t as effective as it could have been.

There was little to no integral approach though, as nobody framed the bigger picture, or provided a framework with which to explore and understand the disparity of topics covered – which included Degrowth, indigenous views, positive tax and understanding energy.

I found myself craving some understanding of human behaviour, and a cohesive theory of change.

Because after all – weren’t we here to explore changing from a growth-at-all-costs model to regrowth?

It also felt like we were stuck in the Do Good Paradigm as outlined by Carol Sanford in her work on the Four Modern Paradigms – Extract Value, Arrest Disorder, Do Good and Regenerate Life.

This was work I was introduced to by Whakaora at the recent Regenerative Summit and it has stuck with me as an embodied way to work with reality that allows life to reveal its potential – which is the same way I work when I’m mentoring clients.

There was plenty of acknowledgment that working from the Extracting Value paradigm was causing major harm to people and planet, and that Arresting Disorder (like Carbon trading Schemes) didn’t go far enough. But without an understanding of human behaviour, or theory of change, I was left wondering, how do the Degrowth people expect populations on mass to suddenly start producing and consuming less?

We can agree that it’s a ‘good idea’ (assuming it is – there’s debate on that), but working from ‘good ideas’ to create change is not effective when there’s no understanding or exploration of the roots of the issue.

Everything in our current culture rewards and is geared towards continuing to extract value whilst producing as much as possible and encouraging mass consumption.

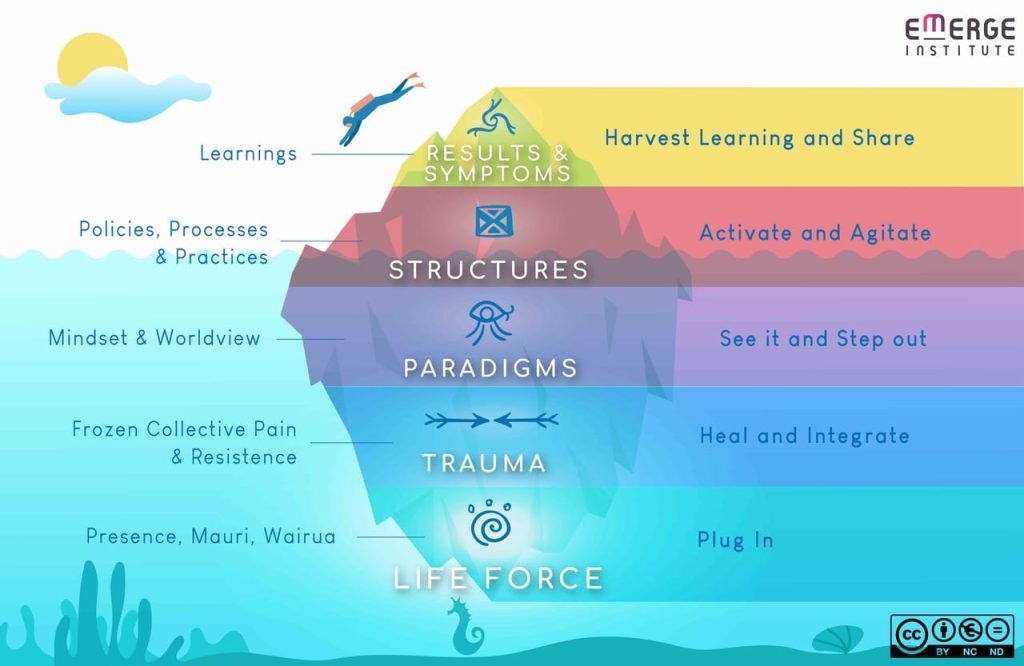

There’s a model that Vinny Lohan shared with me later that day (above), from the Emerge Institute that articulated what I was missing, in detail.

It uses the ubiquitous iceberg to reveal the nature of reality in such a way that we can determine what’s needed to create change at the upper levels – where most of the Degrowth Conference was focused. (See above)

Yes, MC and host Tori McNoe (Te Arawa, Ngāti Tahu/ Ngāti Whaoa/ Ngāti Raukawa/ Pākeha), did mention worldviews once or twice in passing, in a lighthearted way. However the nature of worldviews and their impact on society was never made explicit.

Yet it’s our dominant worldview that Degrowth is challenging. It’s that worldview that Degrowth seeks to change, and to do that, there must be an acknowledgement of the current worldview, but also what’s so damn attractive about it.

Shifting worldviews on a society-wide level is a big endeavour – and it can be done.

It helps that one of the current worldviews in Aotearoa already aligns with much of what regrowth points to – that of Te Ao Māori.

Rangimaria Aperahama’s talk made this explicit when she shared how iwi already holds functional alternatives to growth-focused capitalism and economics. That’s going to be the subject of her PhD, and it’s a reality she’s currently living and embodying as she works with her hapū to ’transform a 15 acre plot of land in the heart of the Kaipara into a Pātaka kai/an abundant food source combining maramataka, tikanga, and mātauranga Māori with permacultural and syntropic practices.’

I loved this intersection between Aperahama’s intellectual work and her embodied actions in the world – this is the kind of leadership we need.

She also pointed out that trade and markets are not synonyms with capitalism, and that early Māori trade was not capitalism.

We segued from Aperahama into Esther Gathombo’s vulnerable and heartfelt talk on the impact of colonisation on Kenya, where she’s from. She spoke about the connections between colonialism, capitalism and the slave trade, and the impact it had, and continues to have on her tribe and family.

I loved how Gathombo iterated that she doesn’t have the answers, but she demonstrated that she knows the territory that we have to explore.

The next two talks were both focused on tax – one from Denise Paterson that was mostly facts and figures and left me craving narrative and sense-making. I realised that my expectation was that a talk at a conference like this wouldn’t just be information but rather would aim to inspire the audience to relate to reality differently and take different actions.

And, when she said, twice, that ‘Nobody wants to pay more tax.’ I wanted to stand up and challenge the assumption in that statement, and challenge the reality she was projecting onto us.

Fortunately, the next speaker Gareth Hughes of the Wellbeing Economy Alliance did just that. He asked us how many of us would pay more tax if we knew it would directly lead to better services for all of New Zealand. Almost every hand in the room went up.

My major takeaway from Hughes’s presentation, which lightly touched on major milestones in New Zealand’s tax history, was the possibility of shifting tax from predominantly on our labour to taxing resources and/or capital.

The final presentation moved away – finally – from the talking heads model and into an interactive workshop. It was hosted by Dark Green Aotearoa, an organisation that ‘seeks to build community resilience through deep adaptation and to upskill themselves in preparation for the discontinuities we can expect from changes to our energy supply, the economy, our society and the environment.’

Despite being excited to move into a workshop setting, I had issues with the underlying assumptions and approach to the workshop. Small groups were given sectors – like education or transport – and asked to map out the system and determine where energy savings or reductions could be made.

This is where I again felt the lack of a cohesive theory of change driving the conference.

Whilst there was some great information and passion in the Dark Green presentation that preceded the workshop, I felt that using an inquiry-based approach using Carol Sanford’s Four Paradigms model would have been more fruitful.

Attempting to save or reduce energy usage within a sector is a top-down symptom and ‘arrest disorder’ approach. I felt like inquiring into the paradigm shifts required to automatically generate a different energy use pattern could have been a more engaging and fruitful approach.

This reveals my particular bias though – of always seeking to determine what the root cause is of any presenting symptom and to deal with that.

That’s where the Emerge Institute framework would have been interesting as a way to frame the entire conference – it starts with Lifeforce (Presence, Mauri, Wairua) at the base, moves up to Trauma (our frozen collective pain and resistance) and into Paradigms (our mindsets and worldviews) before going into Structures (our policies, process and practice) and Results & Symptoms.

Any Theory of Change I’m working with uses this kind of map. For example, if someone comes to me because they’re experiencing overeating, I don’t waste time on structuring and controlling their eating habits, or their buying habits, or their kitchen etc. I go straight to the underlying trauma that is giving rise to this particular coping mechanism.

Heal the trauma, and the need for the overeating dissolves.

It’s the same with culture-wide or society-wide change. We can’t tell people to produce less or consume less because it’s the good thing to do, or the right thing to do. Whilst some people are motivated by their self-identity as a ‘good’ person, it won’t generate social-wide change until we investigate more deeply the paradigms, worldviews, and underlying trauma that’s creating the structures and symptoms we see.

It’s something I’ve often inquired into – for example, what caused colonialism? How could men (it was mostly men) arrive on new land, believe that they had a God-given right to claim that land, extract valuable resources and use whatever means possible to exterminate those humans already living there while believing that they were the superior and good people in that equation?

Humans who feel a deep connection to the land, to life, and to each other, don’t behave that way.

What is the frozen collective pain and resistance underneath the world views that justified the colonial settler actions?

Remember too that those who came to the Americas, to Australia, to Aotearoa… they were completely identified with their worldview as if it was just the way life was. (Although there were a significant number of ‘colonisers’ who ‘went native’ – who left behind their old worldview and assimilated into the worldview of those whom they were there to conquer.)

But back to Beyond Growth!

I love the questions that Degrowth is exploring – how do we reframe the measurements of progress at a political level beyond ever-increasing GDP?

I love that those in the Degrowth movement are embracing indigenous wisdom and worldviews.

I love that the Degrowth people brought us all together to explore this on a Friday afternoon.

Being in that space helped me to see where the thinking is currently at, how it’s being presented, and what might be needed to support the kaupapa that’s emerging.

One of my major takeaways from Jennifer Wilkins talk on Degrowth, which opened, was that we need to shift from progress and growth as a measurement of success to post-growth wellbeing. That we could shift to using a ratio of well-being to resources as THE metric, instead of GDP.

And to do that, she said, the regrowth movement needs better narratives and needs to be more persuasive.

I would add that it needs a theory of change based on an understanding of the nature of reality. And it needs to incorporate other models into its thinking, including the work of Carol Sanford on the Four Modern Frameworks.

When we move from the perspective of supporting the regeneration of life, we open up to evolving inherent potential.

And I love that – it has a completely different embodied feel from trying to or the ‘good;’ or ‘right’ thing.

It implies that we trust life, we trust humanity, we trust that we’ve got this, we just need to open up and do what’s needed to allow it to happen.

That feels possible to me.

How does it feel to you?

Please note: This ‘review’ is more accurately my reflections and learnings, plus next steps explored and articulated in article form. I’ve used the word ‘review’ for SEO purposes, and to entice people to read about the event, through my particular lens, with all its inherent biases and blind spots. What I’ve shared is my observations and direct experience through my filters. It does not accurately reflect what the event was – it’s just one small refracted window of the whole.

Please note: There was one other speaker, who spoke on reclaiming craft as art, and the colonialism of craft, but I neglected to take notes on her name or presentation. I will add that soon!

A Review of Rakiura Rhyme Machine Festival 2023

A Review of Rakiura Rhyme Machine Festival 2023